After their forced relocation and incarceration, many Japanese and Japanese American families found themselves caught in the middle of nations, grappling with what they were told was an impossible dynamic: being American and being of Japanese descent. Though they were civilians living peaceably in the United States, the government determined that their Japanese heritage constituted a national threat. First generation immigrants, along with their second-generation children born in the United States (and thus granted citizenship), were removed from their homes and relocated to incarceration camps regardless of their length of time in the country, citizenship status, or lack of a criminal record.

Incarcerated Japanese and Japanese Americans dealt with intense emotions as their lives were uprooted and they were forced to move. Some wrestled with intense feelings of anger and betrayal. The country they had lived in and loved did not trust them. What would their lives look like moving forward? Some young men wondered if they should return to Japan, while others sought to prove their loyalty to the United States by enlisting in the military. Some historians argue that even within the same family it would not have been uncommon for one son to return to Japan and for another to join the U.S. army. [1]

Within the incarceration camps themselves, many sought to create a sense of normalcy for themselves and for their children with the government’s encouragement. Parents set up schools where their children could learn. Doctors continued to practice medicine and treat patients within the camps. Some, like Ruth Asawa, were granted special permission to leave the camps and attend college.

Many Japanese Americans sketched and painted their experiences and surroundings, giving life to the many conflicting emotions they felt. According to historian Kristine C. Kuramitsu, Japanese American’s artwork served to document the artists’ feelings and to assert their agency and worth when they had been deprived of many of their civil liberties. [2]

Though this was a difficult time for Japanese Americans, their accomplishments during and after their incarceration shows their resilience. This memorial seeks to both honor that resilience and recognize the injustice of Executive Order 9066.

Written by Ruth Truman, SFSU History M.A. 2024

How the Incarceration Affected SFSU Students

Across from the waterfall, there is a bronze scroll that tells the story of the students’ incarceration.

Scans of what is engraved on the bronze scroll. The scroll is read from right to left. The full panel text is available below.

Text from the Bronze Scroll

GARDEN OF REMEMBRANCE

April 19, 2002

This memorial garden commemorates the experiences of more than 120,000 Japanese Americans who were removed from their homes, banished from their communities, and incarcerated during World War II. Without trial or charges of wrongdoing, thousands were held in places such as race track horse stalls before being sent to one of ten inland U.S. camps.

In 1942, nineteen San Francisco State students were among the innocent Japanese Americans who were singled out by their government solely because of their ancestry. In 1998, the University invited the surviving students to attend Commencement and receive public recognition as Honored Alumni of San Francisco State University. This Garden of Remembrance honors those students as well as the courageous faculty and staff who supported them.

Each large boulder symbolizes one of the ten permanent camps in which Japanese Americans were confined. The rock waterfall celebrates the release of the Americans from incarceration and World War II restrictions. In vindicating these Americans' honor, this memorial reinforces our determination that such injustices will never be repeated.

Robert A. Corrigan, President

San Francisco State University

EXECUTIVE ORDER no.9066

AUTHORIZING THE SECRETARY OF WAR TO PRESCRIBE MILITARY AREAS

Whereas the successful prosecution of the war requires every possible protection against espionage and against sabotage to national-defense material, national-defense premises and national-defense utilities as defined in Section 4, Act of April 20, 1918, 40 Stat. 533, as amended by the Act of November 30, 1940, 54 Stat. 1220, and the Act of August 21, 1941, 55 Stat. 655 (U.S.C., Title 50, Sec. 104):

Now, therefore, by virtue of the authority vested in me as President of the United States, and Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy, I hereby authorize and direct the Secretary of War, and the Military Commanders whom he may from time to time designate, whenever he or any designated Commander deems such action necessary or desirable, to prescribe military areas in such places and of such extent as he of the appropriate Military Commander may determine, from which any or all persons may be excluded, and with respect to which, the right of any persons to enter, remain in, or leave shall be subject to whatever restriction the Secretary of War or the appropriate Military Commander may impose in his discretion The Secretary of War is hereby authorized to provide for residents of any such area who are excluded therefrom, such transportation, food, shelter, and other accommodations as many be necessary, in judgement of the Secretary of War of the said Military Commander, and until other arrangements are made, to accomplish the purpose of this order. The designation of military areas in any region or locality shall supersede designations of prohibited and restricted areas by the Attorney General under the Proclamations of December 7 and 8, 1941, and shall supersede the responsibility and authority of the Attorney General under the said proclamations in respect of such prohibited and restricted areas.

I hereby further authorize and direct the Secretary of War and the said Military Commanders to take such other steps as he or the appropriate Military Commander may deem advisable to enforce compliance with the restrictions applicable to each Military area hereinabove authorized to be designated, including the use of Federal troops and other Federal Agencies, with authority to accept assistance of state and local agencies.

I hereby further authorize and direct all Executive Departments, independent establishments and other Federal Agencies, to assist the Secretary of War or the said Military Commanders in carrying out this Executive Order, including the furnishing of medical aid, hospitalization, food, clothing, transportation, use of land, shelter, and other supplies, equipment, utilities, facilities, and services.

This order shall not be construed as modifying or limiting in any way the authority heretofore granted under Executive Order no. 8972, dated December 12, 1941, nor shall it be construed as limiting or modifying the duty and responsibility of the Federal Bureau of Investigation , with respect to the investigation of alleged acts of sabotage or the duty and responsibility of the Attorney General and the Department of Justice under the Proclamations of December 7 and 8, 1941, prescribing regulations for the conduct and control of alien enemies, except as such duty and responsibility is superseded by the designation of military areas hereunder.

Franklin D. Roosevelt

The White House, February 19, 1942

WESTERN DEFENSE COMMAND AND FOURTH ARMY WARTIME CIVIL CONTROL ADMINISTRATION

Presidio of San Francisco, California

April 1, 1942

Instructions to All Persons of Japanese Ancestry Living in the Following Area:

All that portion of the City and County of San Francisco, lying generally west of the of the north-south line established by Junipero Serra Boulevard, Worchester Avenue, and Nineteenth Avenue, and lying generally north of the east-west line established by California Street, to the intersection of Market Street, and thence on Market Street to San Francisco Bay.

All Japanese persons, both alien and non-alien, will be evacuated from the above designated area by 12:00 o’clock noon Tuesday, April 7, 1942.

No Japanese person will be permitted to enter or leave the above described area after 8:00 a.m., Thursday, April 2, 1942, without obtaining special permission from the Provost Marshal at the Civil Control Station located at:

1701 Van Ness Avenue

San Francisco, California

The Civil Control Station is equipped to assist the Japanese population affected by this evacuation in the following ways:

- Give advice and instructions on the evacuation.

- Provide services with respect to the management, leasing, sale, storage or other disposition of most kinds of property including real estate, business and professional equipment, household goods, boats, automobiles, livestock, etc.

- Provide temporary residence elsewhere for all Japanese in family groups.

- Transport persons and a limited amount of clothing and equipment to their new residence as specified below.

The Following Instructions Must Be Observed:

- A responsible member of each family, preferably the head of the family, or the person in whose name most of the property is held, and each individual living alone must report to the Civil Control Station to receive further instructions. This must be done between 8:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m., Thursday, April 2, 1942, or between 8:00 a.m. and 5 p.m., Friday, April 3, 1942.

- Evacuees must carry with them on departure for the Reception Center, the following property:

- Bedding and linens (no mattress) for each member of the family.

- Toilet articles for each member of the family.

- Extra clothing for each member of the family.

- Sufficient knives, forks, spoons, plates, bowls and cups for each member of the family.

- Essential personal effects for each member of the family.

- All items carried will be securely packaged, tied and plainly marked with the name of the owner and numbered in accordance with instructions received at the Civil Control Station.

- The size and number of packages is limited to that which can be carried by the individual or family group.

- No contraband items as described in paragraph 6, Public Proclamation No. 3, Headquarters Western Defense Command and Fourth Army, dated March 24, 1942, will be carried.

- Bedding and linens (no mattress) for each member of the family.

- The United States Government through its agencies will provide for the storage at the sole risk of the owner of the more substantial household items, such as iceboxes, washing machines, pianos and other heavy furniture. Cooking utensils and other small items will be accepted if crated, packed and plainly marked with the name and address of the owner. Only one name and address will be used by a given family.

- Each family, and individual living alone, will be furnished transportation to the Reception Center. Private means of transportation will not be utilized. All instructions pertaining to the movement will be obtained at the Civil Control Station.

Go to the Civil Control Station at 1701 Van Ness Avenue, San Francisco, California, between 8:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m., Thursday, April 2, 1942, or between 8:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m., Friday, April 3, 1942, to receive further instructions.

J. L. DeWITT

Lieutenant General, U. S. Army Commanding

SAN FRANCISCO STATE COLLEGE

INTERDEPARTMENTAL CORRESPONDENCE

To the Faculty,

Our roster shows that we enrolled nineteen Japanese students this spring semester. Already several of them have withdrawn and filed leaving cards. We know certain faculty have made personal arrangements with the individual students for him to complete his work in absentia. If you have made any such arrangements, please report this to us at once so we may post the fact on his record. Without this information we must mark the student withdrawn from your course.

| Arita, Matsume | Koyama, Norman |

| Sato, Dora | Fukushima, Percy |

| Matsuda, Grace | Sutow, Tomiko |

| Hata, Mary M. | Mayeda, Helen |

| Yoshiyama, Tom | Hirose, George |

| Miya, Yoshiko | Yoshino, May |

| Kawamorita, Kathryn | Nishi, Aiko |

| Yusa, Atsuko | Kikuchi, John |

| Nishioka, Akiko | Kitagawa, Kaya |

| Nitta, Helen |

Office of the Registrar

April 6, 1942

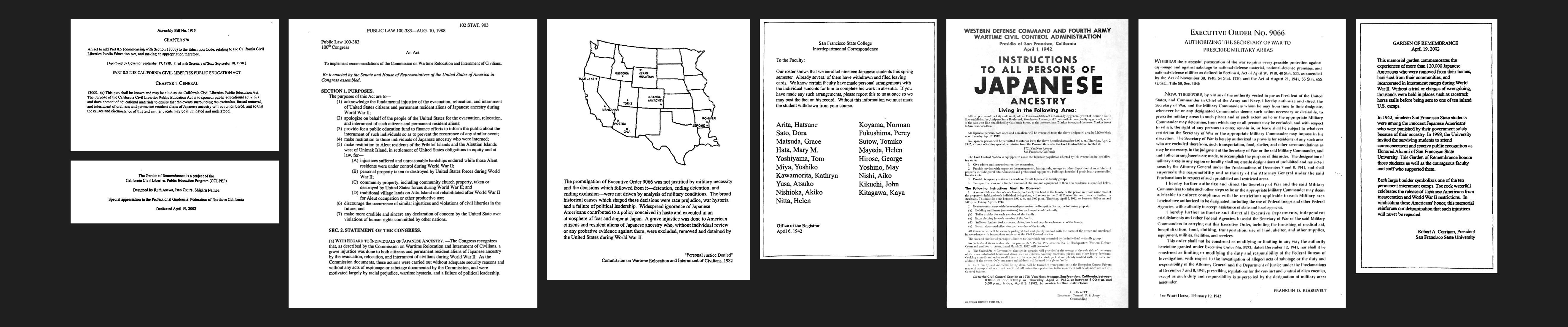

A map of the United States with the location of the ten permanent incarceration camps noted.

The promulgation of Executive Order 9066 was not justified by military necessity and the decisions which followed form it — detention, ending detention, and ending exclusion — were not driven by analysis of military conditions. The broad historical causes which shaped these decisions were race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership. Widespread ignorance of Japanese Americans contributed to a policy conceived in haste and executed in an atmosphere of fear and anger at Japan. A grave injustice was done to American citizens and resident aliens of Japanese ancestry who, without individual review or any probative evidence against them, were excluded, removed and detained by the United States during World War II.

“Personal Justice Denied”

Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, 1982

102. STAT. 903

PUBLIC LAW 100-383 – AUG. 10, 1988

Public Law 100-383

100th Congress

An Act

To implement recommendations of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians.

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of American in Congress assembled,

SECTION 1. PURPOSES.

The purposes of this Act are to —

(1) acknowledge the fundamental injustice of the evacuation, relocation, and interment of United States citizens and permanent resident aliens of Japanese ancestry during World War II;

(2) apologize on behalf of the people of the United States for the evacuation, relocation, and internment of such citizens and permanent resident aliens;

(3) provide for a public education fund to finance efforts to inform the public about the internment of such individuals so as to prevent the recurrence of any similar event;

(4) make restitution to those individuals of Japanese ancestry who were interned;

(5) make restitution to Aleut residents of the Pribilof Islands and the Aleutian Islands west of Unimak Island, in settlement of United States obligations in equity and at law, for —

- (A) injustices suffered and unreasonable hardships endured while those Aleut residents were under United States control during World War II;

- (B) personal property taken or destroyed by United States forces during World War II;

- (C) community property, including community church property, taken or destroyed by United States forces during World War II; and

- (D) traditional village lands on Attu Island not rehabilitated after World War II for Aleut occupation or other productive use;

(6) discourage the occurrence of similar injustices and violations of civil liberties in the future; and

(7) make more credible and sincere any declaration of concern by the United States over violations of human rights committed by other nations.

SEC. 2. STATEMENT OF THE CONGRESS.

(a) WITH REGARD TO INDIVIDUALS OF JAPANESE ANCESTRY — The Congress recognizes that, as described by the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, a grave injustice was done to both citizens and permanent resident aliens of Japanese ancestry by the evacuation, relocation, and internment of civilians during World War II. As the Commission documents, these actions were carried out without adequate security reasons and without any acts of espionage or sabotage documented by the Commission, and were motivated largely by racial prejudice, wartime hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.

ASSEMBLY BILL No. 1915

CHAPTER 570

An act to add Part 8.5 (commencing with Section 13000) to the Education Code, relating to the California Civil Liberties Public Education Act, and making an appropriation therefor.

[Approved by Governor September 17, 1998. Filled with Secretary of State September 18, 1998.]

PART 8.5 THE CALIFORNIA CIVIL LIBERTIES PUBLIC EDUCATION ACT

CHAPTER 1. GENERAL

13000. (a) this part shall be known and may be cited as the California Civil Liberties Public Education Act. The purpose of the California Civil Liberties Public Education Act is to sponsor public educational activities and development of educational materials to ensure that the events surrounding the exclusion, forced removal, and internment of civilians and permanent resident aliens of Japanese ancestry will be remembered, and so that the causes and circumstances of this and similar events may be illuminated and understood.

The Garden of Remembrance is a project of the

California Civil Liberties Public Education Program (CCLPEP)

Designed by Ruth Asawa, Isao Ogura, Shigeru Namba

Special appreciation to the Professional Gardeners' Federation of Northern California

Dedicated April 19, 2022

References

[1] Kristine C. Kuramitsu, “Internment and Identity in Japanese American Art,” American Quarterly 47, no. 4 (December 1995): 621.

[2] Kuramitsu, “Internment and Identity,” 619-58.